Skull

The skull is a bony structure in the head of many animals that supports the structures of the face and protects the brain from injury.

The skull is composed of two parts: the cranium and the mandible. A skull without a mandible is only a cranium. Animals that have skulls are called craniates.

Functions of the skull include protection of the brain, fixing the distance between the eyes to allow stereoscopic vision, and fixing the position of the ears to help the brain use auditory cues to judge direction and distance of sounds. In some animals, the skull also has a defensive function (e.g. horned ungulates); the frontal bone is where horns are mounted.

Contents |

Human skull

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

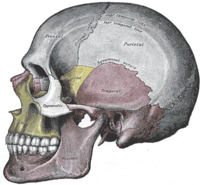

In humans, the adult skull is normally made up of 22 bones. Except for the mandible, all of the bones of the skull are joined together by sutures, rigid articulations permitting very little movement. Eight bones —including one frontal, two parietals, one occipital bone, one sphenoid, two temporals and one ethmoid— form the neurocranium (braincase), a protective vault surrounding the brain. Fourteen bones form the splanchnocranium, the bones supporting the face. Encased within the temporal bones are the six ear ossicles of the middle ears, though these are not part of the skull. The hyoid bone, supporting the tongue, is usually not considered as part of the skull either, as it does not articulate with any other bones. The skull is a protector of the brain.

The skull contains the sinus cavities, which are air-filled cavities lined with respiratory epithelium, which also lines the large airways. The exact functions of the sinuses are unclear; they may contribute to decreasing the weight of the skull with a minimal decrease in strength, or they may be important in improving the resonance of the voice. In some animals, such as the elephant, the sinuses are extensive. The elephant skull needs to be very large, to form an attachment for muscles of the neck and trunk, but is also unexpectedly light; the comparatively small brain-case is surrounded by large sinuses which reduce the weight.

The meninges, or the system of membranes which envelops the central nervous system, are the three membranes which surround the structures of the nervous system. They are known as the dura mater, the arachnoid mater and the pia mater. Other than being classified together, they have little in common with each other.

In humans, the anatomical position for the skull is the Frankfurt plane, where the lower margins of the orbits and the upper borders of the ear canals are all in a horizontal plane. This is the position where the subject is standing and looking directly forward. For comparison, the skulls of other species, notably primates and hominids, may sometimes be studied in the Frankfurt plane. However, this does not always equate to a natural posture in life.

Other skulls

Tetrapod skulls

The skull of the earliest tetrapods closely resembles that of their ancestors amongst the lobe-finned fishes. The skull roof is formed of a series of plate-like bones, including the maxilla, frontals, parietals, and lacrimals, among others. The various separate bones that compose the temporal bone of humans are also part of this series. A further plate composed of four pairs of bones forms the roof of the mouth; these include the vomer and palatine bones. The base of the cranium is formed from a ring of bones surrounding the foramen magnum and a median bone lying further forward; these are homologous with the occipital bone and parts of the sphenoid in mammals. Finally, the lower jaw is composed of multiple bones, only the most anterior of which (the dentary) is homologous with the mammalian mandible.[1]

In living tetrapods, a great many of the original bones have either disappeared, or fused into one another in various arrangements. In mammals and birds, in particular, there have been modifications of the skull to allow for the expansion of the brain. The fusion between the various bones is especially notable in birds, in which the individual structures may be difficult to identify . Living amphibians typically have greatly reduced skulls, with many of the bones either absent or wholly or partly replaced by cartilage.[1]

Temporal fenestrae

The temporal fenestrae are anatomical features of the skulls of several types of amniotes, characterised by bilaterally symmetrical holes (fenestrae) in the temporal bone. Depending on the lineage of a given animal, two, one, or no pairs of temporal fenestrae may be present, above or below the postorbital and squamosal bones. The upper temporal fenestrae are also known as the supratemporal fenestrae, and the lower temporal fenestrae are also known as the infratemporal fenestrae. The presence and morphology of the temporal fenestra is critical for taxonomic classification of the synapsids, of which mammals are part.

Physiological speculation associates it with a rise in metabolic rates and an increase in jaw musculature. The earlier amniotes of the Carboniferous did not have temporal fenestrae but two more advanced lines did: The Synapsids (mammal-like reptiles) and the Diapsids (most reptiles and later birds). As time progressed, diapsids' and synapsids' temporal fenestrae became more modified and larger to make stronger bites and more jaw muscles. Dinosaurs, which are sauropsids, have large advanced openings and their descendants, the birds, have temporal fenestrae which have been modified. Mammals, which are synapsids, possess no fenestral openings in the skull, as the trait has been modified. They do, though, still have the temporal orbit (which resembles an opening) and the temporal muscles. It is a hole in the head and is situated to the rear of the orbit behind the eye.

Classification

There are four types of amniote skull, classified by the number and location of their fenestra. These are:

- Anapsida - no openings

- Synapsida - one low opening (beneath the postorbital and squamosal bones)

- Euryapsida - one high opening (above the postorbital and squamosal bones); euryapsids actually evolved from a diapsid configuration, losing their lower temporal fenestra.

- Diapsida - two openings

Evolutionarily, they are related as follows:

Skulls in fish

Although the skulls of fossil lobe-finned fish resemble those of the early tetrapods, the same cannot be said of those of the living lungfishes. The skull roof is not fully formed, and consists of multiple, somewhat irregularly shaped bones with no direct relationship to those of tetrapods. The upper jaw is formed from the pterygoids and vomers alone, all of which bear teeth. Much of the skull is formed from cartilage, and its overall structure is reduced.[1]

In the ray-finned fishes, there has also been considerable modification from the primitive pattern. The roof of the skull is generally well-formed, and although the exact relationship of its bones to those of tetrapods is unclear, they are usually given similar names for convenience. Other elements of the skull, however, may be reduced; there is little cheek region behind the enlarged orbits, and little, if any bone in between them. The upper jaw is often formed largely from the premaxilla, with the maxilla itself located further back, and an additional bone, the symplectic, linking the jaw to the rest of the cranium.[1]

Cartilaginous fish, such as sharks, have a much simpler, and presumably more primitive, skull structure. The cranium is a single structure forming a case around the brain, enclosing the lower surface and the sides, but always at least partially open at the top as a large fontanelle. The most anterior part of the cranium includes a forward plate of cartilage, the rostrum, and capsules to enclose the olfactory organs. Behind these are the orbits, and then an additional pair of capsules enclosing the structure of the inner ear. Finally, the skull tapers towards the rear, where the foramen magnum lies immediately above a single condyle, articulating with the first vertebra. There are, in addition, at various points throughout the cranium, smaller foramina for the cranial nerves. The jaws consist of separate hoops of cartilage, almost always distinct from the cranium proper.[2]

The structure is simpler still in lampreys, in which the cranium is represented by a trough-like basket of cartilagenous elements only partially enclosing the brain, and associated with the capsules for the inner ears and the single nostril. Distinctively, these fish have no jaws.[2]

Gallery

A hippopotamus' skull |

A Tyrannosaurus skull |

A cat skull, a typical skull of a carnivore |

Killer whale (Orcinus orca) |

A lion's skull, another typical carnivore |

A bulldog skull |

A raccoon's skull |

Alligator skull |

A Grizzly bear's skull |

A coypu skull, a typical rodent |

A gerbil skull, another typical rodent |

A Cervocerus novorossiae skull |

|

Paracyclotosaurus davidi |

A Four-horned antelope skull drawing |

A Vulture skull, a typical bird |

See also

- Anatomical terms of location

- Bone terminology

- Craniometry

- Head and neck anatomy

- Phrenology, the pseudoscientific process of determining personality from the shape of the head.

- Skull (symbolism)

- Plagiocephaly, the abnormal flattening of one side of the skull.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 216–247. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 173–177. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

References

- White, T.D. 1991. Human osteology. Academic Press, Inc. San Diego, CA.

External links

- Skull preparation and curation (Information about skull and skeleton cleaning and articulation, with photos)

- Skull Maceration tutorial (Information on cleaning skulls and skeletons by maceration)

- Anatomy of cranial cavity.

- Dept of Anth Skull Module

- Skull Anatomy Tutorial.

- Human Skulls / Anthropoligical Skulls / Comparison of Skulls of Vertebrates (PDF; 502 kB)